It has been reported in recent weeks that the owners of Arsenal, Chelsea and Liverpool are looking for football clubs to add to their portfolios.

We have written before on the growing number of groups pursuing a multi-club ownership model and noted the trend-setting approach of City Football Group (CFG) and Red Bull. According to recent articles, the US-based owners of Arsenal, Chelsea and Liverpool are all looking to mirror the CFG approach, with Chelsea’s Todd Boehly perhaps the most vocal on his strategic intention.

Owners taking stakes in a number of clubs is not new to football. Red Bull’s acquisition of SV Austria Salzburg in 2005 was followed the following year by that of the New York/New Jersey MetroStars (rebranded the New York Red Bulls) and then in 2009 by the purchase, renaming (as RB Leipzig) and subsequent bankrolling of fifth tier SSV Markranstädt, propelled through four promotions in seven years to finish second in the Bundesliga in the 2016/17 season. The Pozzo family, owners of Serie A side Udinese since 1986, added Championship club Watford to their stable in 2012, while Vincent Tan bought Cardiff City, FK Sarajevo and KV Kortrijk – and took a 20% stake in Los Angeles FC – between 2010 and 2015. As for CFG, after buying Manchester City in 2008 the group acquired a franchise for the MLS (New York City) in 2013 – the team entered the competition in 2015 – and have gone on to buy stakes or full ownership in a further 10 men’s clubs and Manchester City Women, assuming the prospective acquisition of Esporte Clube Bahia in Brazil’s second tier goes through.

Many owners of European football clubs already have multiple sports assets in their portfolios. In the Premier League alone, seven clubs are partly- or fully-owned by parties which have at least one asset in one of the four major US sports leagues. But the emerging approach is to focus specifically on football clubs.

Why multi-club ownership?

The multi-club ownership model can benefit owners in numerous ways, the most obvious being player scouting, acquisition and development. Through a network of clubs in different countries, each with a local technical department, owners are well positioned to spot emerging talent and use the prospect of playing for flagship clubs in major leagues to attract emerging stars. Players can also be sent on loan “in house” rather than being trusted to clubs where managers may play them out of position or not at all, hampering their development. Pathways can be created through leagues of increasing quality and challenge for potential superstars with close monitoring throughout their development, while a consistent style of football can be adopted across the group to prepare them ahead of a move to a new club. Through their multi-club scouting model the Pozzo family have identified an impressive list of quality players over the years, amongst them Alexis Sanchez (bought for just £500k), Samir Handanović and Mehdi Benatia (both free transfers), Asamoah Gyan, Odion Ighalo, Sulley Muntari, Oliver Bierhoff and Gokhan Inler.

The financial benefits of the multi-club ownership (MCO) system come through the ability to acquire players inexpensively in the early part of their career rather than being at the mercy of the transfer market, the avoidance of loan fees (or at least keeping them within the group) and the management of player wages at a portfolio level. By centralising key departments – both technical and commercial – the organisation can operate more effectively and efficiently, while accumulating learning from a wide range of leagues and quickly reapplying successful models. Commercially, MCOs can offer multi-country partnerships to sponsors, build brand awareness globally (especially through common branding such as the use of the City suffix or Red Bull name) and cross-fertilise support between groups of fans.

The “Smaller Five”

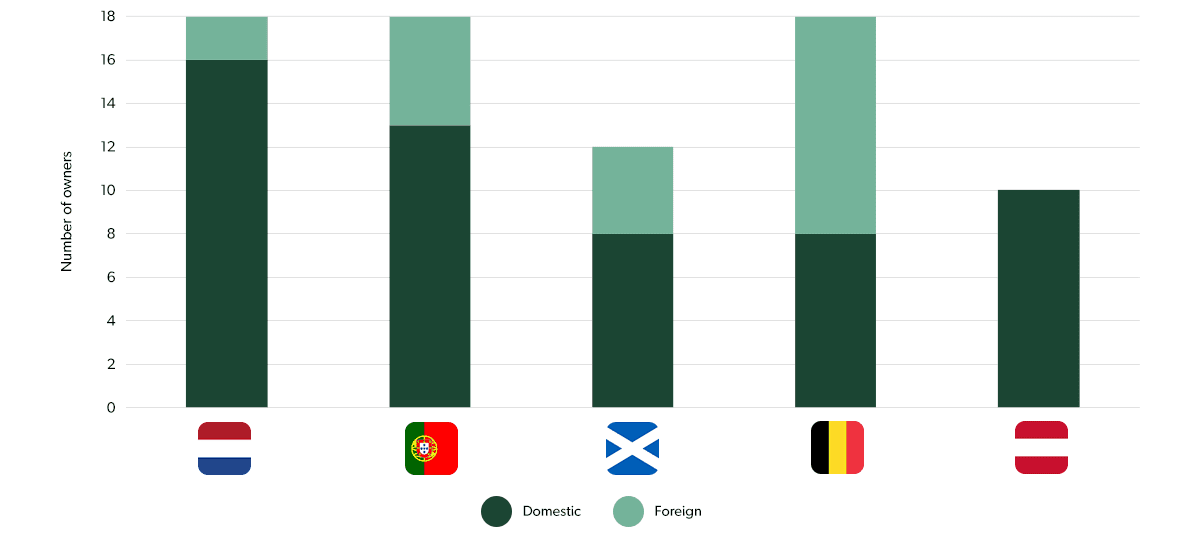

Let’s look at some of the most promising European leagues outside the “Big Five” to find clubs for a portfolio – countries six to 10 in the UEFA rankings. Of course, many groups have acquired clubs in lower tiers of European markets (and beyond), but for the purposes of this article we will focus on the top tier only. These leagues have already been subject to significant M&A activity involving overseas entities, in particular Belgium’s Pro League where significant stakes have been taken by foreign investors in 10 of 18 clubs. These include six MCOs including Pacific Media Group (which has stakes in seven clubs), 777 Partners (four), King Power (owners of Leicester City), Tony Bloom (Brighton & Hove Albion) and Vincent Tan (Cardiff City). It should also be noted that clubs in the Austrian Bundesliga are subject to similar “50+1 rule” constraints on external investment as their counterparts in Germany, but they remain in the analysis on the basis that this may change in the future.

10 of Belgium’s top-tier clubs (2021/22 season) are owned by overseas investors

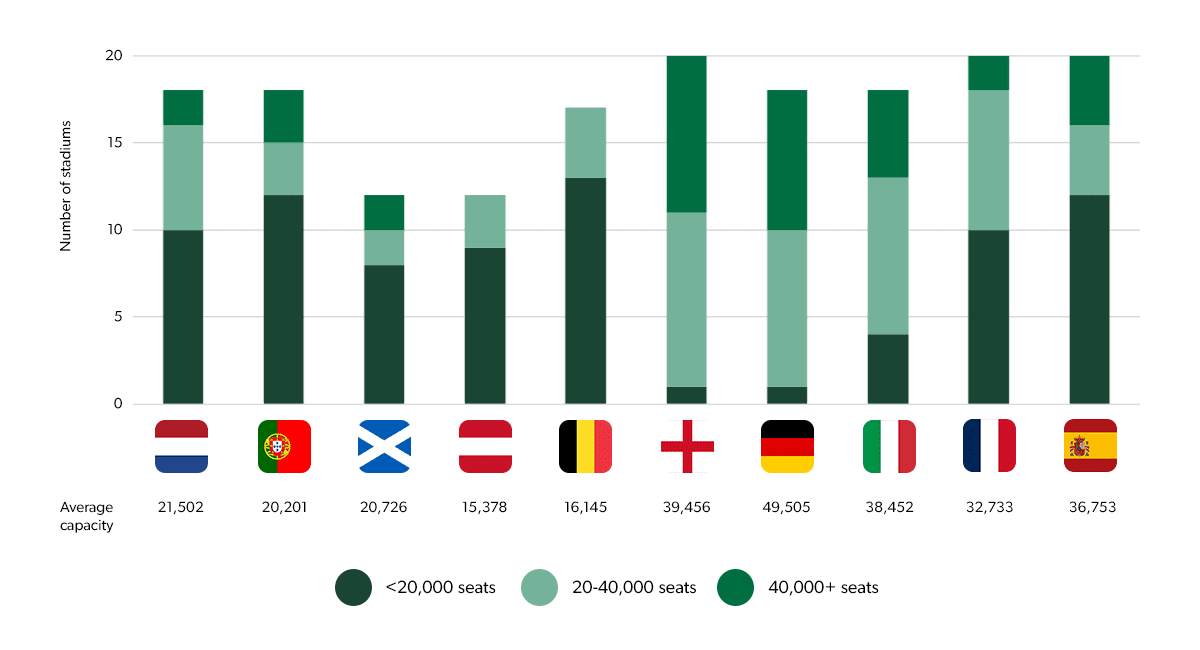

Let’s start by looking at key club assets – the stadium and the squad. From a stadium perspective, Holland’s Eredivisie is the best positioned, with an average stadium capacity of 21.5k including eight venues with more than 20,000 seats. Portugal and Scotland have an average capacity of a little over 20k, although it is worth noting that of the 12 stadia with up to 20,000 seats, eight have fewer than 10,000 (and average 6,500), while the three 50,000+ stadia of FC Porto, Sporting CP and SL Benfica bring the overall average up. Austrian and Belgian stadia are smaller on average at 16.1k and 15.4k respectively. Relative to the biggest European leagues, the “Smaller Five” have significantly fewer large stadia – the Premier League and Bundesliga have only one each of this size – although at least half the members of the French and Spanish leagues have stadia with fewer than 20,000 seats.

The Dutch Eredivisie has eight stadia with a capacity of over 20,000

Source: Transfermarkt

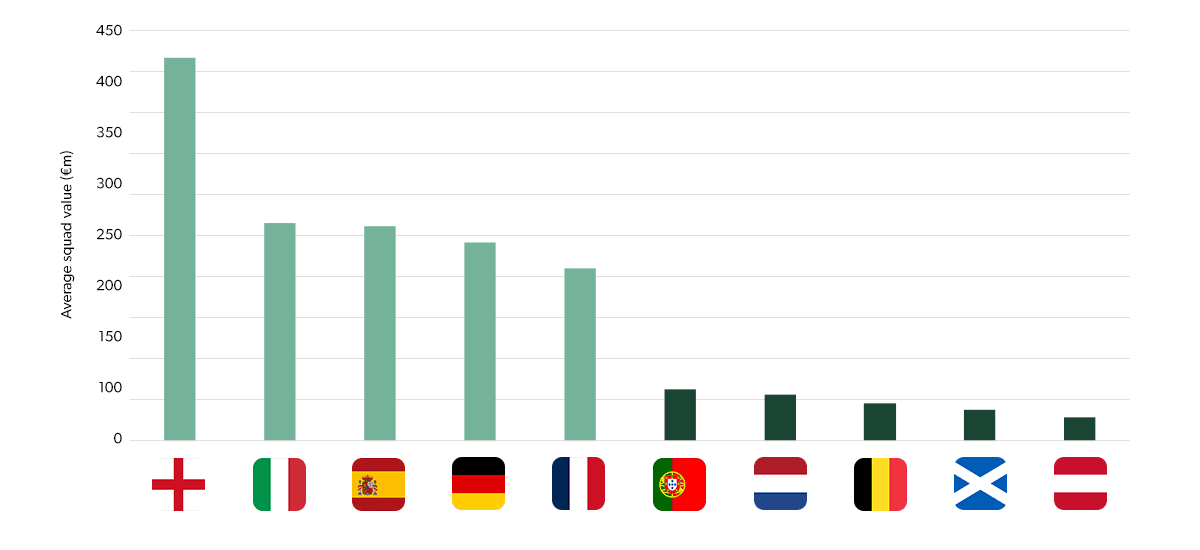

Turning to squad value, Portuguese clubs come out on top with an average squad value of €63.6m in the 2021/22 season, ahead of Holland with €56.6m. Meanwhile the smallest league on this measure is Austria, where clubs have a roster of players worth €28.2m on average. These numbers are dwarfed by the Big Five: the average Premier League club’s squad value was €466.9m in the same season, while the other four largest leagues had squads averaging between €210m – €265m.

Portuguese and Dutch top-tier clubs have an average squad value above €50m

Source: Transfermarkt

Revenue streams

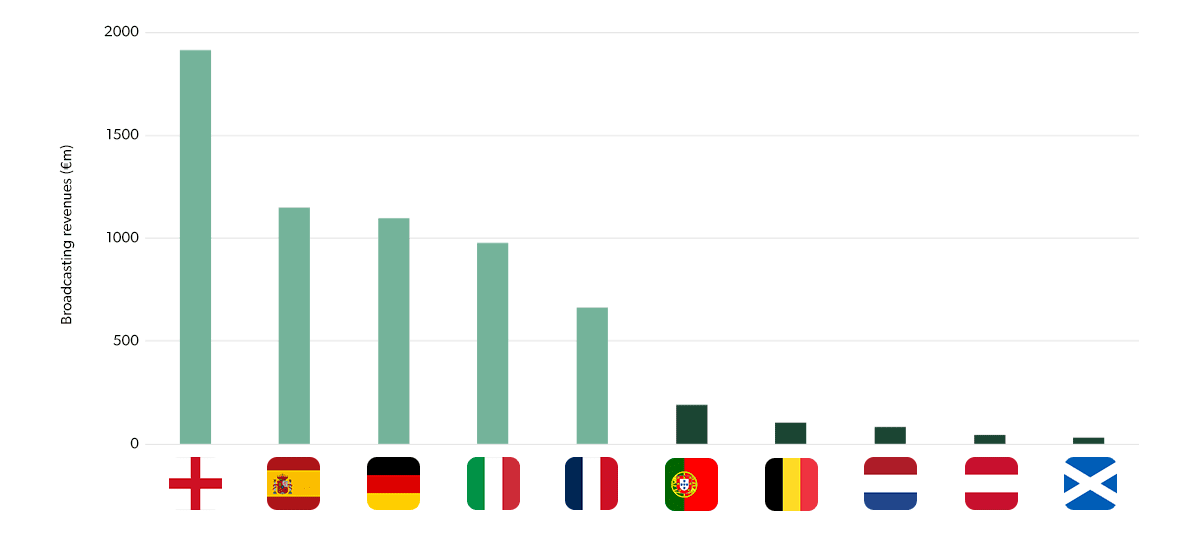

Let’s look now at the key revenue streams, starting with broadcasting revenues. Again, Portugal is in the strongest position, with estimated annual revenues for domestic rights in the range of €180m to €210m. These are negotiated individually by the clubs and not all contract figures are available. Importantly, the big three clubs have the power to secure the lion’s share of TV money, with contracts estimated at €125m between them, accounting for 60-70% of total league broadcasting revenue.

Elsewhere, media contracts are negotiated collectively by the leagues, and achieve lower annual revenues, ranging from €103m per season in Belgium to just €29m in Scotland, where a proposed new deal with Sky Sports (to start in the 2024/25 season) would see an increase to €35m per season with a higher number of games broadcast per season.

The Portuguese Primeira Liga has the highest domestic broadcasting revenue amongst the “Smaller Five”

Source: Tifosy analysis

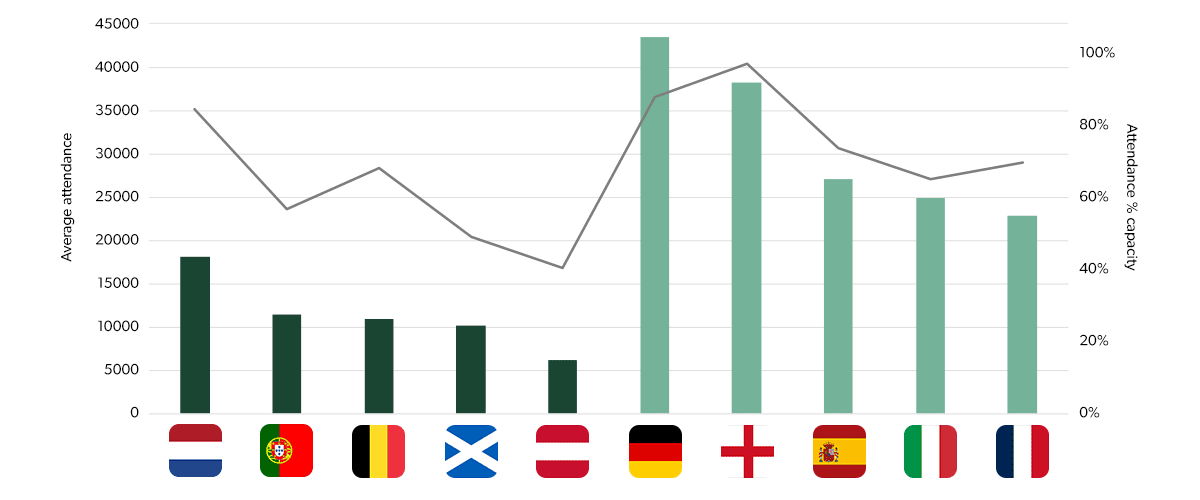

As well as having the highest average stadium capacity and the highest number of large (20,000+ seat) stadia, the Netherlands also tops the table for match attendance, with an average of 18.2k per match, which equates to 84% of capacity. By comparison, Portuguese clubs manage only 11.5k on average, or 57% of capacity, while the clubs of the Belgian Pro League achieve 68% of capacity but an absolute average of 11.0k. Attendances in neither Scotland nor Austria reach 50% of capacity on average.

The Dutch Eredivisie boasts the highest average attendance in absolute and as a percentage of capacity

Source: Transfermarkt

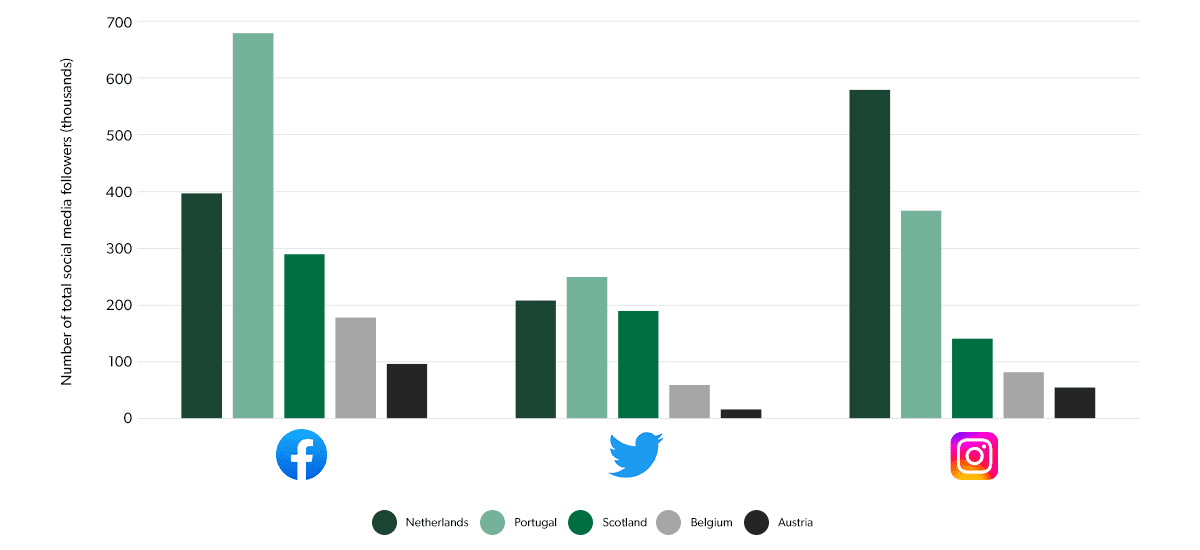

Social media following can be used as a proxy for size of fanbase, and on this measure it is Portugal which stands higher than the rest. Portuguese clubs average 679k followers on Facebook, 249k on Twitter and 366k on Instagram – an overall non-deduplicated following of 1.3m. Clubs in the Dutch Eredivisie outperform them significantly on Instagram with 579k but are smaller on the other platforms, totalling 1.2m overall. In third place are Scottish clubs, while those of Belgium and Austria are significantly further behind.

Portuguese clubs are the most developed on social media

Source: Tifosy analysis

Finally, we look at net income from buying and selling players in the transfer market. It is no surprise to see the “Big Five” spending significantly more than they make on selling players, with the rich clubs of the Premier League collectively accruing a net spend of €4.6bn over the past five years – although the Ligue 1 in France actually achieved a higher net income than all but one of the “Smaller Five” in the same period.

Portuguese clubs are known for identifying and developing players and selling them on to larger clubs at elevated prices, but it is actually Austria’s Bundesliga – on many other measures the smallest of the “Smaller Five” – which has generated the highest net income from the transfer market, selling €392m of players and spending only €126m over the past five years.

Austria’s Bundesliga has the highest net transfer income over the past five years

Source: Transfermarkt